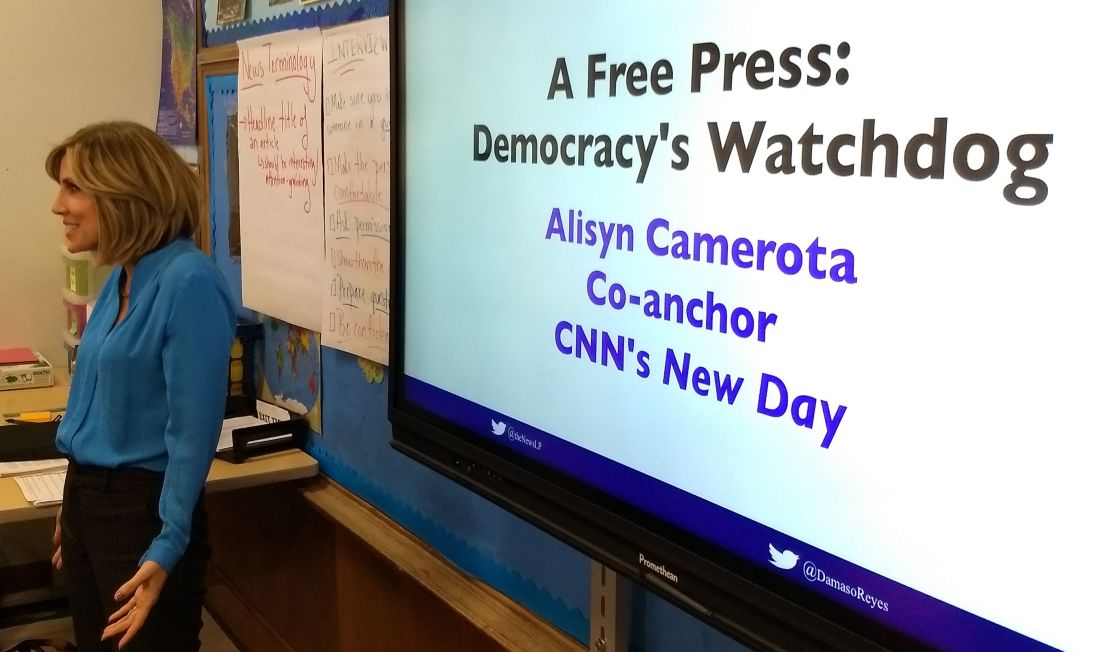

Editor’s Note: Alisyn Camerota is a CNN anchor and co-host of CNN’s morning show, “New Day.” She is a member of the national advisory council of the News Literacy Project, a nonprofit that gives students in grades 6-12 the skills to sort fact from fiction in the digital age. The views expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Imagine being a kid today: wandering through the Wild West of media where professional journalists, citizen reporters, user-generated content and fake news all coexist online. The information landscape has exploded exponentially as kids try to have their news needs met by sources like Reddit and Hacker News, not to mention micro-targeted websites, blogs and podcasts.

So, whom do they actually trust?

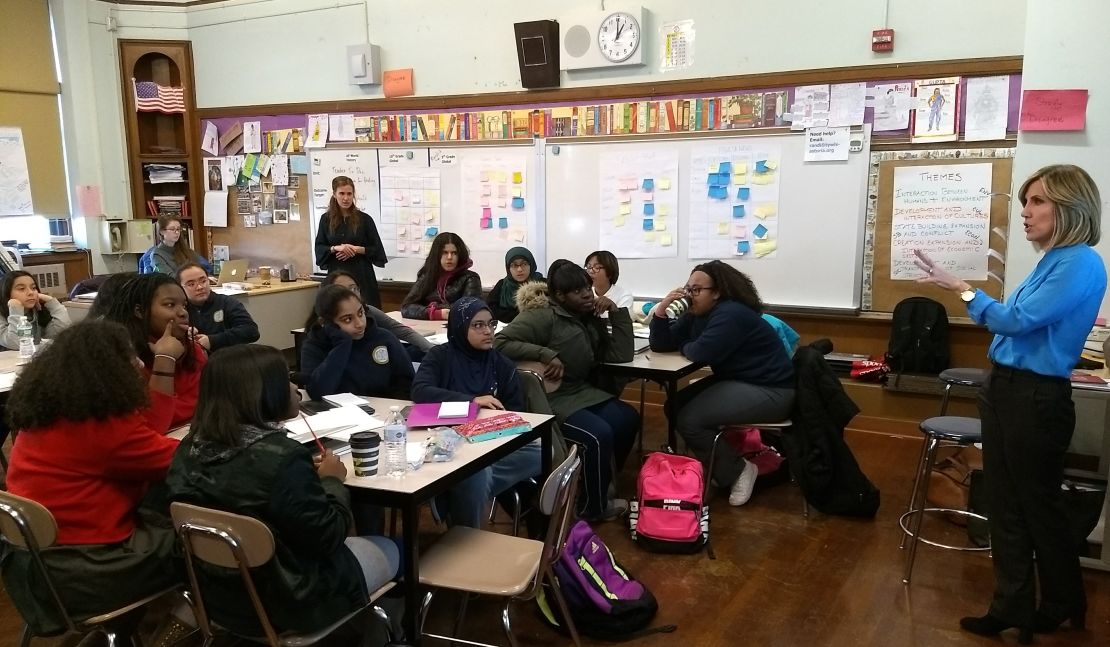

To find out, I went to the Young Women’s Leadership School, an all-girls public school in Queens, New York. There, I had a chance to ask 5th, 6th and 7th graders about their news sources. These students were starting the school’s first newspaper, so they were the perfect focus group. I dove right in, thinking I’d cleverly start with social media. Turns out, I had some catching up to do.

“Where do you all get your news?” I asked. “Show of hands for Twitter.”

No one moved a muscle.

“Um … Facebook?” I tried.

Blank expressions. You could have heard a thumbtack drop – if they still used those.

Their teacher finally clued me in. “Snapchat,” she said. “Everyone has Snapchat.”

“What now?” I asked.

Snapchat, they told me, lets you read headlines and some articles – including, they gently explained, from CNN.

“And what do you do if you want to know more than just headlines?” I asked.

They looked at each other, then at me.

“You just …” one student started, then paused, “… don’t.”

These students are not alone. Snapchat is the most popular social media site among teens, according to a December 2017 social media survey by RBC Capital. 79% of teenaged respondents have accounts. It’s also growing in popularity as a news source, a September 2017 Pew Research Center study found – 29% of the app’s users get news there, up from 17% in 2016.

I found this unnerving. Let’s face it, not all sites or apps are following the tried and true news rule of being vigilantly fact-based. And kids, it turns out, have a hard time discerning fact from fiction. A 2016 study published by Stanford University of more than 7,800 US middle school, high school and college students found that at least 80% of them were unable to distinguish credible reporting from biased information or complete falsehoods. The same study found that 80% of middle school students can’t tell the difference between “sponsored content” (advertising) and a news article.

If only they taught a course in this stuff.

Enter the News Literacy Project (NLP), a national education nonprofit that gives middle school and high school students the tools they need to be smarter news consumers. I’ve had the opportunity to see NLP in action – including at the Young Women’s Leadership School, where students use NLP’s virtual classroom to figure out what news and information to trust and share versus what to debunk and delete. Here are some of their tips:

- What’s your first reaction to something you’re reading, watching or hearing: Are you outraged? Excited? Curious? Misinformation peddlers know that emotional appeals can overwhelm rational thought.

- Take a close look at the source (news outlet, blog, video producer, etc). Does it have an “About Us” page (or something similar) that explains who runs the site? Is there a disclaimer on the site noting that everything on it is satire or fiction? Is there something odd about the URL? Fake news sites may use URLs that are similar to real ones – but slightly off.

- Do a reverse image search on photos and graphics: Have they appeared elsewhere online? Do they appear to have been altered? Digital tools and “create a fake” websites make it easy for anyone to falsify or manipulate an image, social media posts, news reports, videos – really, just about anything.

But the virtual classroom isn’t the only answer. Kids, like adults, need to have a balanced news diet – one that challenges their own world view and encourages them to be skeptical. This includes credible sources – for international, national and local news, entertainment news and more – that cover both what you like to click on (the latest celebrity sighting, a human interest story) and what you need to know (national politics, local news, tomorrow’s weather.)

Of course, with the vast amounts of media available, there is a fine line between a healthy news diet and information overload. So, how can students strike this balance? Not all information is created equal, which means kids need to learn how to recognize quality journalism that meets certain standards, such as having multiple sources and verified facts, being balanced, being fair, avoiding bias and putting information in context.

The good news is that basic news literacy training can make a profound impact on the way students evaluate and absorb the news. According to NLP assessment data, the majority of students who have participated in their program reported gaining a greater appreciation for the watchdog role of a free press in a democracy and developing a better understanding of quality journalism and what distinguishes it from other sources of information.

I’m happy to report that endless choice doesn’t have to be overwhelming. The next generation is learning how to navigate the news deluge. And, of course, the kids have a lot to teach me as well. Now if only I can figure out the geofilter on Snapchat.